- Details

The Black Country's aspirations to become the UK's next Geopark hung in the balance earlier this month, at a meeting of eminent geologists in Shetland.

Geopark status is a UNESCO designation and the geological equivalent of being a World Heritage Site. Not only must an area have outstanding geology, but it must have a clear plan for how it can make best use of the geology as an economic and heritage asset.

The Black Country certainly scores on the outstanding geology, having perhaps more diverse stratigraphy than any area of equivalent size in the world. In particular the fossil beds in and around Dudley's Wren's Nest National Nature Reserve are of massive global importance. From a heritage perspective, the role of the Black Country in the Industrial Revolution and its rich legacy of industrial archaeology tick the box. As for economic links, the Black Country stance of making the best of all its heritage assets and putting the quality of its environment at the heart of its regeneration is another strong argument.

In short, after a tour-de-force presentation by Dudley Museum's keeper of geology, Graham Worton, followed by two days of detailed cross-examination, the Black Country cam good, and has been invited to make a formal submission to UNESCO for Geopark status. If you are still sceptical, take a look at the PROJECT WEBSITE.

- Details

To continue on the dark skies theme, I was upset to have missed the spectacular aurora last week - visible as far south as Norfolk. I actually got the amber alert from Aurora Watch but assumed it wasn't strong enough to be seen here. Ho hum! Lancaster University runs the Aurora Watch website, the chart below shows recent magnetic activity, the more activity, the more likely an aurora.

- Details

We recently took a family holiday in the Isle of Skye. After a couple of months of unrelenting cloud and rain for the island, we were blessed with some clear, bright days as a huge high pressure crossed the UK. We also had several cloudless nights, and the northwest of Skye has some of the darkest skies in the UK. The Moon was out of sight, so Jupiter was the brightest object, in the middle of Gemini, with Orion nearby. Once away from any streetlights, the milky was clearly visible, arching overhead to Cassiopeia.

Just using my digital camera I was able to get some nice pictures of constellations and Jupiter’s moons, but as a novice in astrophotography there’s still some way to go.

The most striking thing is to think that, until the industrial revolution, whenever the night sky was clear, it would have been ablaze with stars, wherever you were. Even until the mid-20th century, most people would have enjoyed what are, paradoxically, termed ‘dark skies’.

Light pollution doesn’t just spoil our view of the stars, they disrupt the patterns of animal behaviour – have you never heard a blackbird singing at midnight under city-centre streetlights?

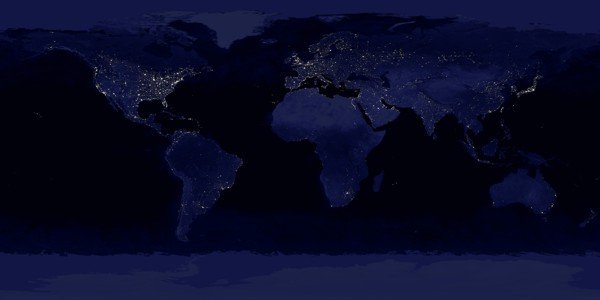

What one really must wonder about, is why we waste so much energy (and money) shooting a large proportion of our outdoor lighting straight up into the sky? Photographs of the night side of Earth from space show the enormous glow spread along the American east and west coasts, across Europe and all the concentrations of cities and industry.

In the USA there are now regulations to limit the upwards spill of light, even so, how long will it be before everyone can see the stars from their front doorstep?

- Details

One of the most exciting projects I have been involved with of late is the possible restoration of the Bradley Canal. This is a curious little canal that once linked between the Wolverhampton and Walsall Canals. In common with many of the Black Country’s minor navigations a mile of it was filled in, so now only a blind branch runs to Bilston from the Wolverhampton Canal, and there’s a short overgrown section adjacent to Moorcroft Wood on the Walsall Canal end.

I was first introduced to this little bit of forgotten waterway perhaps eight or nine years ago, and I naively thought how it would be good to see it brought back into use. I didn’t dig very deep and it seemed that there were many more high profile canal restorations clamouring for attention. Not least of these is the Lichfield to Hatherton Canal – if you have driven along the M6 Toll (or beside it on the A5) you may have seen the ‘canal bridge to nowhere’ east of Brownhills. Unconnected on either side, Britain’s shortest section of canal is just this bridge over the toll road, patiently waiting for the new cut to arrive.

But with Bradley, for a host of reasons: navigation, regeneration, the relatively modest scale and, not least, the putting a wetland wildlife corridor back into the urban landscape, there are signs that the Bradley Canal may be on the way back. Over the next few months the West Midlands Waterway Partnership with the Inland Waterways Association and the Wildlife Trust will be commissioning a feasibility study as the first step towards a full restoration.

UE

Page 4 of 5